A South African government official posing as a racist white woman on Twitter posted several racially incendiary tweets that were designed to spark outrage. The furor generated by these tweets was used to funnel users to at least three of his websites, where he hoped to net an income off the back of the outrage caused by his tweets.

Anthony Matumba, employed by the Makhado Local Municipality in the northern province of Limpopo, is also a member of the radical left Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) political party, well known for its outspoken views on racism and racial inequality. Matumba has registered multiple websites in his name, which he monetized using Google’s AdSense.

In order to drive traffic to these sites and increase the ad revenue they generated, several Twitter accounts spammed links to the websites, mostly in reply to prominent Twitter personalities. One of these accounts, @TracyZille, quickly rose to dubious prominence due to the racist tweets it put out in late June 2020.

Using race as a vector for the spreading of disinformation is nothing new. In March 2020, CNN reported on a Russian troll farm operating out of Ghana, which targeted African Americans in campaigns meant to stir racial tensions. Macedonian click-farms exploited both sides of divisive issues, including race and immigration, during the 2016 U.S. elections and steered the traffic to their revenue-generating websites.

Individuals are more vulnerable to disinformation when the topic confirms their pre-existing biases, including on race and identity. In addition, a study from April 2020 by researchers in China concluded that anger accelerates both the spread and reach of disinformation.

Exploiting racial tensions in South Africa

The exploitation of South African racial tensions was the central tenet of a campaign by the now-defunct British PR firm Bell Pottinger in 2016. The aim of Bell Pottinger’s campaign was to position the Gupta brothers — three well-connected businessmen with close ties to then-president Jacob Zuma — as victims of “white monopoly capital” in an attempt to draw attention from media exposés regarding their own corrupt conduct.

The campaign eventually led to Bell Pottinger’s downfall, as more sordid details of the operation came to light. The PR firm set up blogs, websites and used traditional media campaigns to juxtapose black and white economic interests, framing “white monopoly capital” as the antagonist responsible for the economic hardship facing most black South Africans.

Disinformation campaigns leveraging racial tensions are especially effective in South Africa because of the economic fault lines between white and black South Africans. A disproportionate number of black South Africans are unemployed, owing to the legacy of Apartheid and the African National Congress’ developmental failures.

To Helen back

This presented fertile ground for the @TracyZille Twitter account, created on June 29, 2020. At the time of publication it had amassed nearly 30,000 followers. The name appears to be a homage to Helen Zille, the federal chairperson of South Africa’s main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance and herself a frequent cause of outrage on Twitter.

A screengrab of the @tracyzille Twitter account’s profile as at July 6, 2020, prior to its growth in followers. (Source: @TracyZille/archive)

The @TracyZille account began posting racially provocative content shortly after it was created. It framed these tweets as “advice” offered by a white woman to her peers, generally based on some racist premise.

For example, the most engaged-with tweet published by the account suggested white men were preferable to black men on the basis of being more fit and that black women “throw themselves” at white men. It juxtaposed “hot and fit” white men with overweight black men, and claimed this was the reason black women preferred whites.

Another tweet urged white South Africans to avoid the effects of harmful hand sanitizers (which itself appears to be a COVID-related hoax) by sending their black domestic workers to shop for them. The tweet in essence normalized exposing black people to severe injury so whites can sit back and be served by “garden boys” and “maids.”

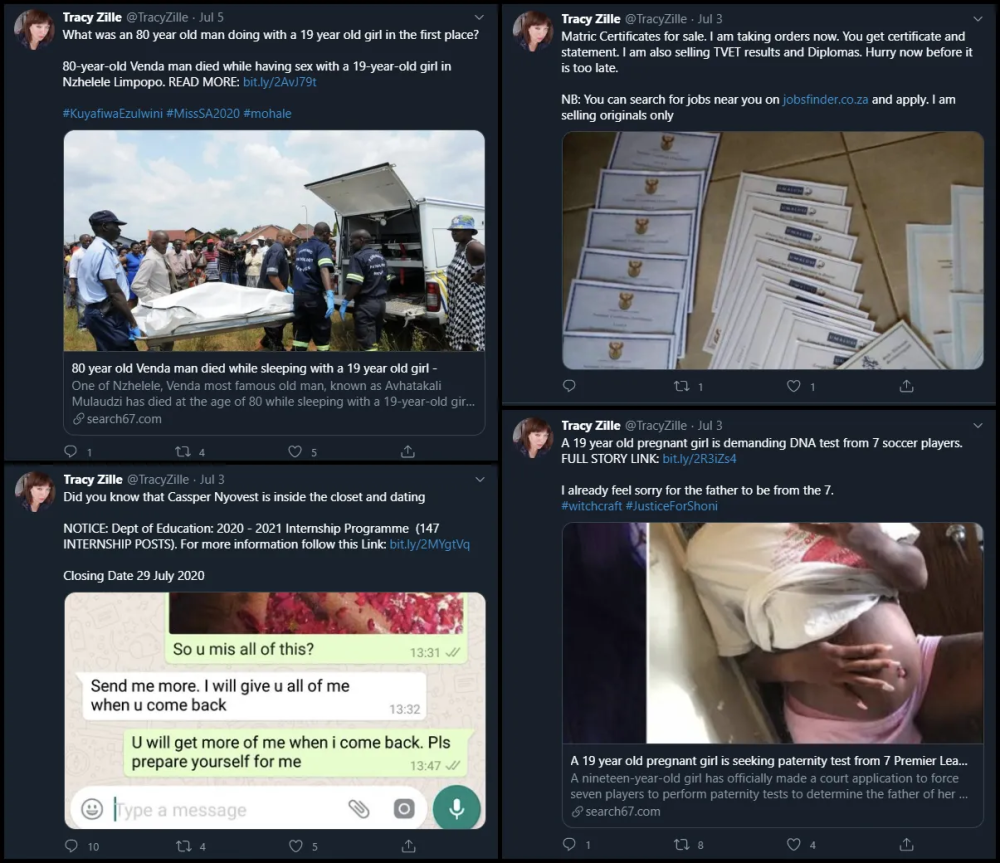

Screengrabs of tweets by the @tracyzille account featuring racist and clickbait content. (Source: @tracyzille/archive, top left; @tracyzille/archive, top right;@tracyzille/archive, bottom left; @tracyzille/archive, bottom right)

Screengrabs of tweets by the @tracyzille account featuring racist and clickbait content. (Source: @tracyzille/archive, top left; @tracyzille/archive, top right;@tracyzille/archive, bottom left; @tracyzille/archive, bottom right)

The account also posted several clickbait links featuring sensational stories. Some claimed South African celebrities were involved in sex scandals, or aspired to be white, while other tweets claimed to provide details on the South African Social Security Agency’s COVID-19 relief grant. All of these articles and headlines were designed to grab the eye.

Screengrabs from tweets posted by @TracyZille containing links to several websites associated with Matumba. The posts and headlines were generally lurid and macabre clickbait. (Source: @tracyzille/archive, top left; @tracyzille/archive, top right; @tracyzille/archive, bottom left; @tracyzille/archive, bottom right)

Screengrabs from tweets posted by @TracyZille containing links to several websites associated with Matumba. The posts and headlines were generally lurid and macabre clickbait. (Source: @tracyzille/archive, top left; @tracyzille/archive, top right; @tracyzille/archive, bottom left; @tracyzille/archive, bottom right)

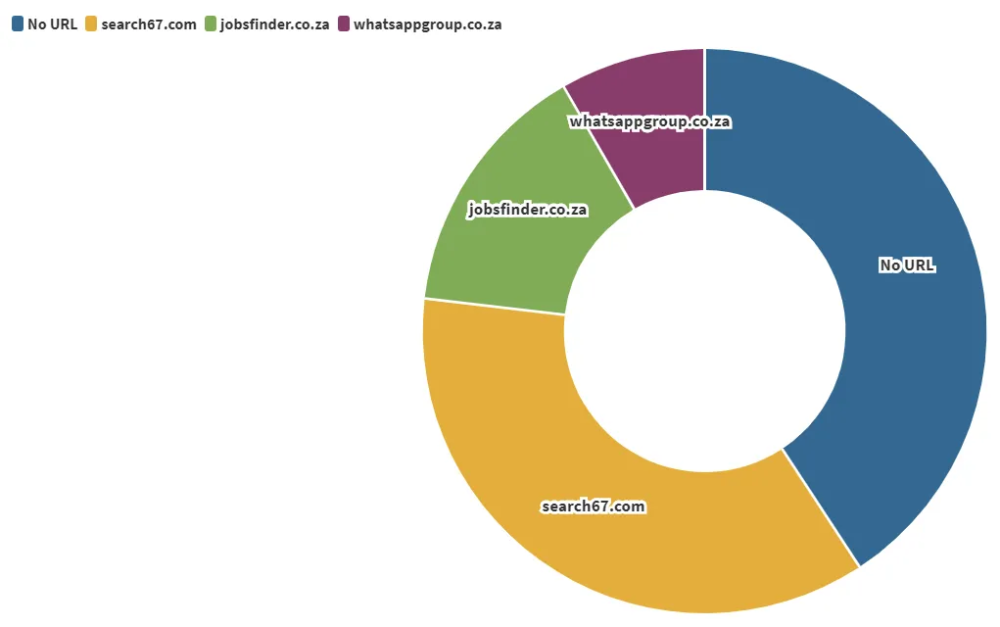

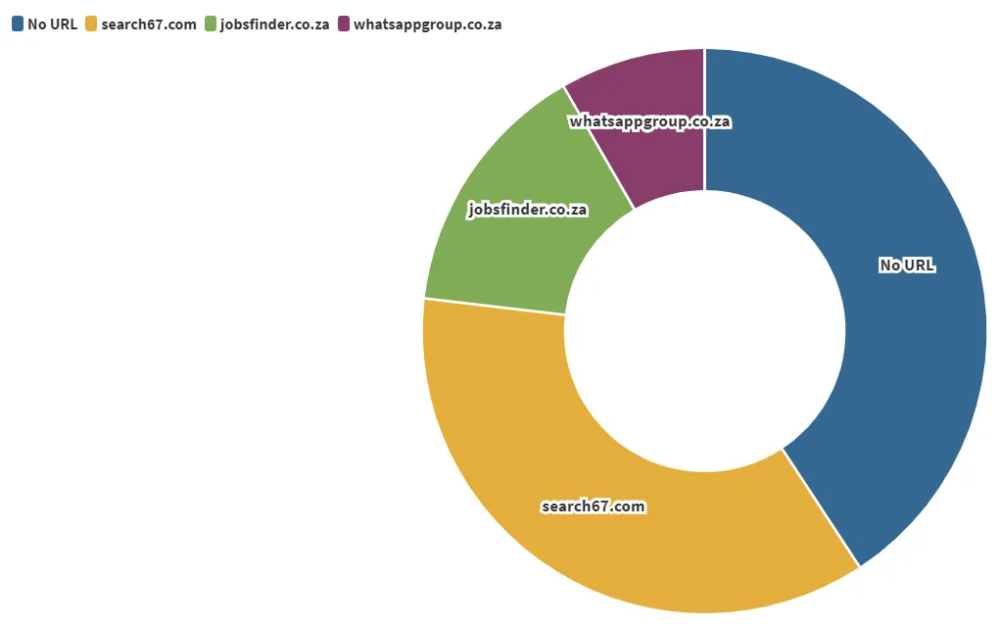

Drawing links

A review of the @TracyZille profile revealed that the account frequently tweeted links to the same three websites. Of the 104 tweets by @TracyZille the DFRLab collected between June 29 and July 4, 61 contained links to one of only three websites: whatsappgroup.co.za, search67.com, and jobsfinder.co.za.

When visiting the sites, a user is bombarded with advertisements delivered using Google’s AdSense platform, which provides tailored adverts according to each visitor. This means that any traffic directed to any of these three websites would become monetized and generate revenue for the owner of the website.

Contact tracing

Considering that the objective of this network appeared to be the amplification of these three websites, an investigation by the DFRLab tried to establish their owners.

Although the link has been removed from the website’s main page, a Contact Us page can still be found by manually changing the URL in the browser’s address bar. This revealed interesting contact information, including that the website is “a news publication” published by a company called Volongonya (Pty) Ltd.

A screengrab from the Contact Us page for the search67.com website retrievable by manually pointing the URL to this page. (Source: search67.com/archive)

Company registration details available from South Africa’s Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) confirmed that this company exists and has a single director: Anthony Matumba. More detailed credit records and employment details confirmed Matumba’s address as that listed in the contact details of search67.com, and confirmed his employment by the Makhado Local Municipality in Limpopo.

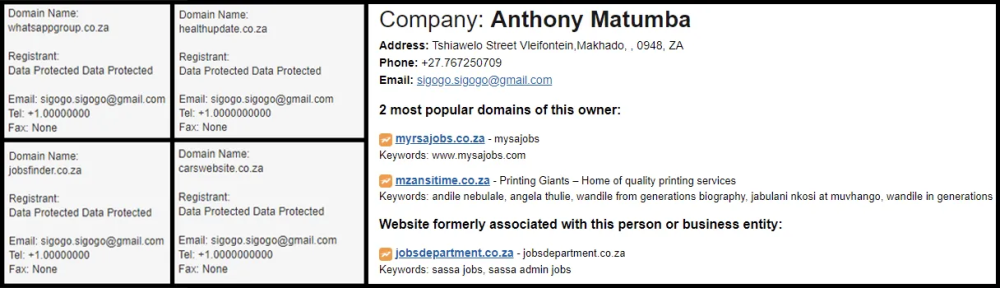

Website registration details also linked Matumba to the other websites amplified by @tracyzille and the rest of the network. Since the page source code of the websites revealed the Google AdSense and Google Analytics codes associated with the three websites, the DFRLab could use these to make further connections.

Jobsfinder.co.za and Search67.com used the same Google Adsense identifier, along with two other websites. This means that the revenue generated by any of the sites would accrue to the same user account and is a strong indication that the sites are connected. Furthermore, WhatsAppgroup.co.za and Jobsfinder.co.za shared the same Google Analytics code, an identifier used by site owners to track visits and user analytics to their website.

The Google Adsense ID (red) and Google Analytics ID (green) for search67.com (left), jobsfinder.co.za (centre) and whatsappgroup.co.za (right) reveal the links between the three pages. (Source: @jean_leroux/DFRLab)

Although domain registration information was limited due to GDPR restrictions imposed by domain registration authorities, historical registration data revealed that an email address, sigogo.sigogo@gmail.com, was used to register jobsfinder.co.za the website. The same email address was used to register several other websites, some under the name of “Anthony Matumba.” The address provided on Website Informer matched the physical address indicated on the Contact Us section of Search67.com.

Historical whois results obtained from Cutestat.com (left) and Website Informer (right) for several websites linked to Matumba through Google Adsense, and Analytics IDs revealed the same e-mail address was also associated with Matumba’s number and e-mail address. (Source: @jean_leroux/DFRLab)

Public servant

Matumba’s name, email address, and cellphone number appear on the EFF’s official website, where he is listed under the party’s “additional members.” Matumba is also featured on the People’s Assembly website, a repository for details of South African political party members, as the 43rd candidate on the EFF’s list of representatives for the northern province of Limpopo.

Matumba’s Facebook and Twitter profiles, both of which make his political affiliation clear, were also identified, and he used both accounts to share links to Search67.com in the last month.

Screengrabs from the Facebook (left) and Twitter (center, right) accounts for Anthony Matumba also revealed he shared links to Search67.com and Whatsappgroup.co.za as early as February 2020. (Source: @jean_leroux/DFRLab)

The author of the articles on search67.com, Abel Mushi, is a suspected pseudonym used by Matumba when posting to his site. A search of Matumba’s Facebook page shows he knew an “Abel Mushi” and thanked him for teaching him about computers in a Facebook post made on July 23, 2019.

Screengrabs from search67.com (left) and Matumba’s Facebook page (right) show that Matumba and the “author” of the search67.com website have a history. (Source: @jean_leroux/DFRLab)

These associations — the company details, the website registration, and AdSense information, and the sharing of links to these sites from his personal profile — place Matumba at the center of these websites, and the ultimate beneficiary of any revenue they generate.

A larger network

The DFRLab also performed a broader analysis on the domain names linked to Matumba after it appeared that a network is involved in amplifying links to his websites. This relatively small network targets influential South African Twitter accounts by replying to their tweets with links to the three websites linked to Matumba.

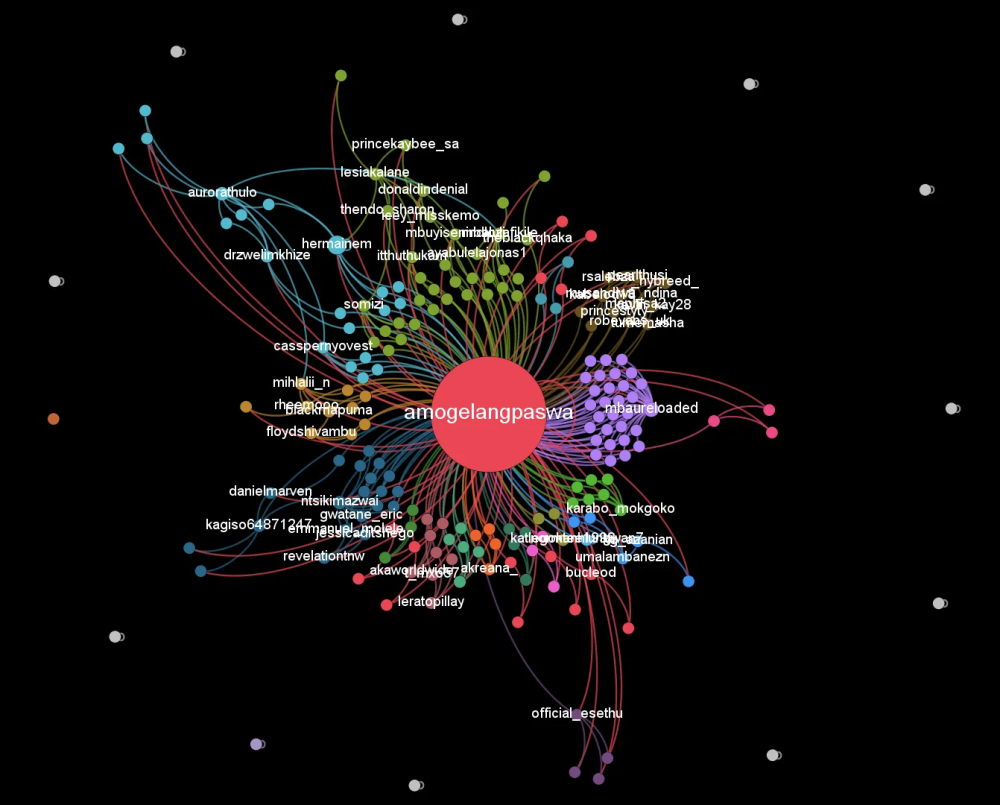

To map the network, the DFRLab harvested tweets containing links to several of the websites traced to Matumba and performed a graph analysis on the collected data using Gephi.

A Gephi visualization of tweets containing links to websites associated with Matumba. The circles (nodes) indicate individual Twitter accounts sized according to the number of tweets that linked to Matumba’s websites, and the lines (edges) are replies or mentions, colored according to its source. (Source: @jean_leroux/DFRLab via Gephi)

What this revealed was a network, mostly propagated by the Twitter account @amogelangpaswa, targeting prominent South African Twitter accounts by replying to their tweets with links to Matumba’s websites. The idea, it seems, is to draw on the large followings of these accounts as a means to amplify the reach of the websites. The @TracyZille account was not included in the above dataset. It appears that the account has been “shadowbanned” by Twitter, which means it is excluded from appearing in search results.

Screengrabs from several tweets linking websites associated with Matumba in replies to prominent South African Twitter accounts. (Source: @jean_leroux/DFRLab via Twitter)

Other accounts such as @MbaliZuma and @AuroraThulo also exhibited the same behavior seen in the @tracyzille and @amogelangpaswa accounts, although to a much lesser extent. Both of these accounts also featured links to Matumba’s websites in their bio fields.

Screengrabs from two of the accounts involved in the coordinated link sharing both contain links to websites associated with Matumba. (Source: @MbaliZuma1/archive; @amogelangpaswa/archive)

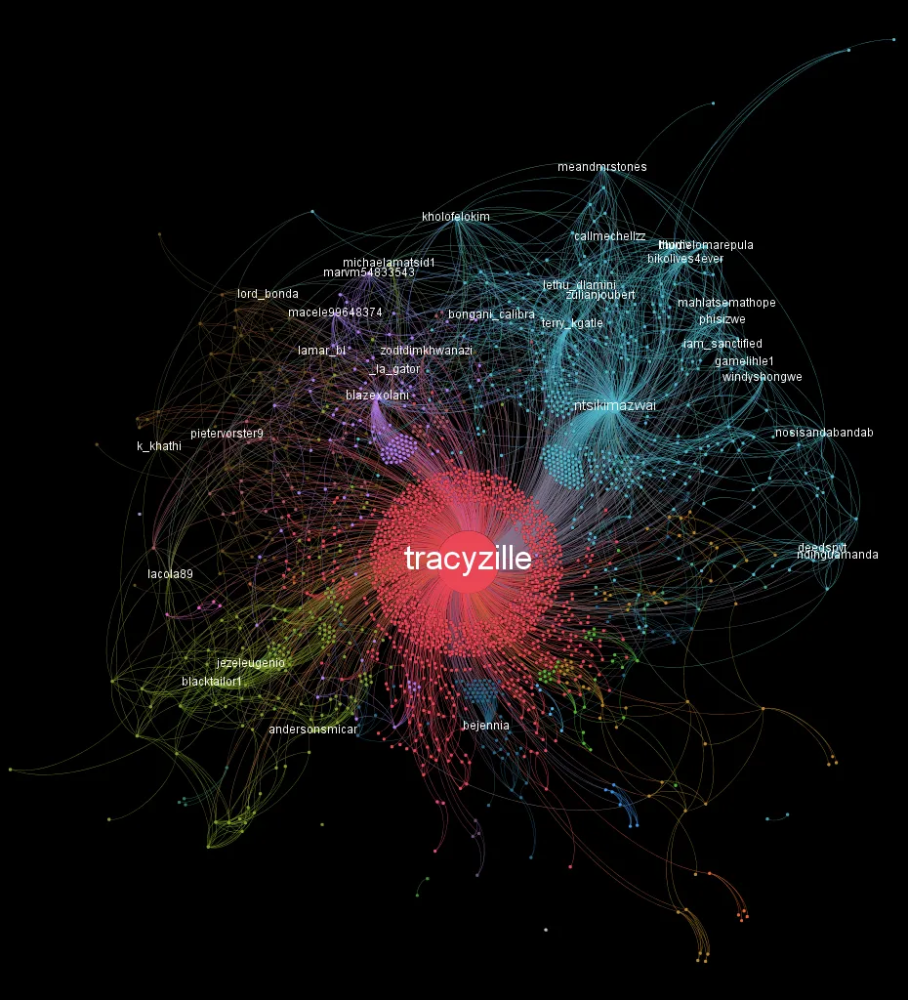

Performing a similar analysis on mentions of the @tracyzille account reveals a similar pattern, with @tracyzille often using the reply function to target prominent users in a similar manner to @amogelangpaswa, @MbaliZuma and @AuroraThulo. This appears to be part of a coordinated effort to amplify the websites in questions, increasing traffic to the sites and consequently the revenue generated for the owner.

An analysis of all mentions of @tracyzille until July 4, 2020. The network shows a large number of replies to @tracyzille in response to his provocative tweets. The network top right (blue) came about after @tracyzille was mentioned by @ntsikimaswai in response to one of his tweets. (Source: @jean_leroux/DFRLab via Gephi)

This appears to be part of a coordinated effort to amplify the websites in questions, increasing traffic to the sites and consequently the revenue generated for the owner. The deployment of racist rhetoric as a lever to propagate disinformation serves to not only undermine legitimate concerns around race and identity, but also exacerbate existing racial tensions. This is of particular concern when an elected leader and government official, tasked with upholding democracy and the good of his constituency, willfully participates in such conduct for narrow personal gain.

Written by Jean le Roux

Jean Le Roux is a Research Associate, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab, and is based in South Africa.

The DFRLab team in Cape Town works in partnership with Code for Africa.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.