South Africa’s main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), launched its election manifesto on 17 February 2024.

According to party leader John Steenhuisen, the DA has a credible path to national government for the first time in 30 years if enough voters turn out on 29 May.

Should the party make it to the highest office, it has a rescue plan ready. The DA says it will save South Africans from unemployment, the energy and water crisis, crime, poverty, failing services and poor education and health systems.

In setting out the issues the country faces in these areas, the DA made several claims. As with the manifestos of other political parties, including Rise Mzansi and the Economic Freedom Fighters, we have fact-checked some of them.

According to the DA, the cadre deployment policy of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) of appointing party loyalists to government positions has led to “the demise” of South Africa’s cities and towns.

“Of the 257 municipalities in South Africa, 151 are on the brink of financial collapse as they cannot pay their creditors, and 43 have already collapsed and are in crisis,” the DA claimed.

South Africa has 257 municipalities: eight metropolitan, 44 district and 205 local. As the level of government closest to the people with a direct impact on their daily lives, including through the provision of essential services, their finances are often scrutinised.

In his budget speech in February 2024, finance minister Enoch Godongwana said that an unacceptable number of municipalities had weaknesses in governance and financial management.

We have asked the DA for the sources of the claims made in its manifesto. We have not yet received a response but we will update this report when we do.

However, the same claim has often been made in the media, with the figures attributed to the national treasury. Briefing a parliamentary committee in September 2022, the treasury said that at the end of the 2021/22 financial year, 151 municipalities were bankrupt and insolvent. This meant that they were unable to pay creditors and third parties such as the South African Revenue Service. A further 43 were in “crisis”.

52% of all councils owed creditors more money than they had in the bank

To see if more recent data was available, we contacted the Auditor-General of South Africa (AGSA), the country's highest audit institution.

An AGSA spokesperson, Khutsafalo Mnisi, directed Africa Check to its most recent general report on local government. This also covered the 2021/22 fiscal year. Its figures are in line with the treasury’s. Of the 241 municipalities audited by the AGSA, 70 were in a financial position “so dire that they had to disclose significant doubt about their ability to fully operate in future”.

Of the 217 municipalities with audit outcomes other than disclaimed or adverse – among the most damaging opinions auditors can give – 56% (some 122 municipalities) showed financial strain. “If not attended to, this can result in significant doubt about their ability to continue operating,” the report said.

The report found that by the end of 2022, 52% of all municipalities (around 133) owed their creditors “more money than they had available in the bank”.

According to AGSA, the main sources of revenue for most municipalities are rates and taxes paid by property owners and consumers of municipal services. But consumers, including government institutions, are not paying municipalities what they owe. This has been a trend for many years, says the auditor.

Other reasons why municipalities lose money include poor payment practices, unfair or uncompetitive procurement practices, and fraud committed by officials.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) compiles annual unemployment statistics for 190 countries, territories and areas of the world. It uses the same definition of unemployment as Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), the national data agency.

According to the latest ILO data, South Africa had the highest unemployment rate of all the economies measured, at 28.8% in 2022. It was followed by Djibouti (26.7%), the West Bank and Gaza (24.4%) and Botswana (23.6%). South Africa has been among the top ten countries in terms of unemployment since 2006.

But as with many statistics, cross-country comparisons can be tricky. Dr Neva Makgetla, a senior economist at the Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies research institute, previously told Africa Check that the definition of unemployment depends on how people in different regions look for work.

According to the ILO, countries use different types of surveys, questions and sampling techniques. All these variations can lead to different results.

The best publicly available data indicates that South Africa has one of the highest unemployment rates in the world. However, it is important to keep caveats about the data in mind.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) compiles annual unemployment statistics for 190 countries, territories and areas of the world. It uses the same definition of unemployment as Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), the national data agency.

According to the latest ILO data, South Africa had the highest unemployment rate of all the economies measured, at 28.8% in 2022. It was followed by Djibouti (26.7%), the West Bank and Gaza (24.4%) and Botswana (23.6%). South Africa has been among the top ten countries in terms of unemployment since 2006.

But as with many statistics, cross-country comparisons can be tricky. Dr Neva Makgetla, a senior economist at the Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies research institute, previously told Africa Check that the definition of unemployment depends on how people in different regions look for work.

According to the ILO, countries use different types of surveys, questions and sampling techniques. All these variations can lead to different results.

The best publicly available data indicates that South Africa has one of the highest unemployment rates in the world. However, it is important to keep caveats about the data in mind.

The working age population is a key driver of a country's economic productivity and growth. South Africa, like many other countries, defines it as people aged 15 to 64.

Stats SA counts as “unemployed” those who were able to work, wanted to find work and were actively looking for work at the time of its surveys. At the end of 2023, the unemployment rate was 32.1%.

However, not all people of working age are actively participating in the labour market. Some have a job, some are looking for a job and some are discouraged. Others are fully engaged in other activities or have no interest in the labour market.

But for the proportion of the working-age population that is employed, the absorption rate is a better indicator, economist Makgetla previously told Africa Check. This indicator includes people aged 15 to 64 who did paid work for at least an hour or had a job or business in the week of the survey.

At the end of 2023, the labour absorption rate was 40.8% of the working age population, meaning that only four in ten people reported that they did have a job. This means that well over a third of South Africa’s working age population is “out of jobs”.

The absorption rate includes people of working age who may not be able to work. If we consider only those who were able to work but were discouraged from looking for work (for example, because there were no jobs nearby) or had other reasons for not actively looking for work, the latest unemployment rate is 41.1%.

Whichever way you slice it, the DA underestimated how many people are out of work, missing an opportunity to make an even stronger case for the depth of the problem.

Murder statistics are published by the South African Police Service (SAPS) on a quarterly and annual basis. From April 2022 to March 2023, the SAPS reported 27,494 murders, a slightly higher number than the DA claimed.

If the figures from the individual quarterly reports from this period (Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4) are added up, the total comes to 27,272, as the party claimed.

However, according to Lizette Lancaster, an analyst at the Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies (ISS), quarterly publications should ideally not be used to calculate annual data. The annual reports contain the “official and verified” statistics for each year, Lancaster told Africa Check.

The DA went on to claim that between April 2022 and March 2023, South Africa recorded the highest annual murder rate ever.

The annual murder rate is not the same as the number of murders in a given period. The rate takes into account changes in the country’s population. As we’ve written before, most recently when fact-checking Rise Mzansi’s manifesto, experts use this measure to assess trends over time.

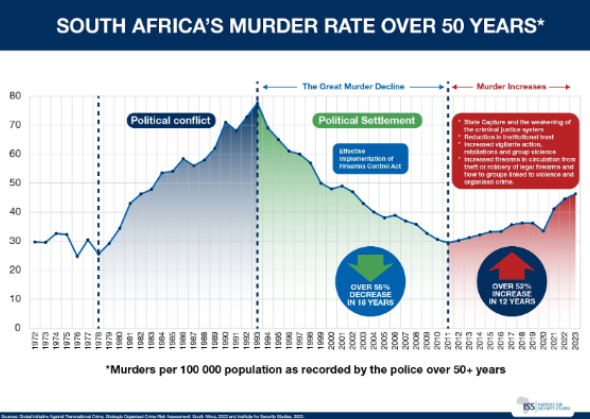

The murder rate is calculated as the number of murders per 100,000 people in the population. In 2022/23, the murder rate was around 45 per 100,000 people. This is considered extremely high and is part of a wider trend of steadily increasing murder rates in the country since a low point around 2011.

Highest murder rate in history was around 1993

Although this rate is high, it is still much lower than in the past, as the graphic below from the Institute for Security Studies shows.

Data on murder before 1994 is limited and varies between sources. This likely led to a “large undercount” of murders throughout the 20th century, according to a 2019 Global Study on Homicide by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Despite these problems, the study concluded that the data could be used to look at longer-term trends in South Africa’s murder rates. The authors wrote that “contrary to popular perception”, South Africa’s high murder rate is “by no means a post-apartheid phenomenon”.

In fact, although murder rates have risen since the report was published, they are still far lower than they were around 1993. This was confirmed by Anine Kriegler, a researcher at the ISS and a contributor to the 2019 study. “The best available data indicates that the highest murder rate in South Africa’s history was around 1993,” Kriegler told Africa Check.

Exact figures vary depending on the source and population estimates used, but around 1993 the murder rate was estimated to be in the high 70s, 80s or even 90s per 100,000 people.

The increase from the 1950s was a result of apartheid policies, Kriegler explained in the study: “Large-scale forcible removals destroyed communities and social networks, caused widespread trauma and entrenched poor conditions and spatial exclusion.”

The increase continued as political conflict intensified in the 1980s and 1990s. From 1994 onwards, rates plummeted, until the mid-2010s, when they began to rise again.

A simple definition of literacy is the ability to read and write in at least one language. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization defines literacy as “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, compute and use printed and written materials”.

This type of literacy is typically measured in terms of the developmental outcomes expected at particular grades in school. Internationally, students in grade 4 are expected to be able to read for meaning. This means that they should be able to read, process, contextualise and understand the message of a text.

The Progress in Reading and Literacy Study (PIRLS) is an international benchmark assessment, conducted every five years, that measures students’ reading skills at a grade 4 level.

In South Africa, students’ reading literacy is tested in 11 of the country’s 12 official languages, with the exception of South African Sign Language.

The 2021 assessment, the most recent, shows that South Africa’s performance was poor, with very few students scoring above the lowest benchmark. Over 80% of grade 4 students could not read to locate and retrieve explicit information.

Source: PIRLS 2021 Main Report

The assessment found a link between students' scores and resources at home, such as books and study aids. Students with more resources available to them achieved higher scores.

The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) is an international assessment of the mathematical and scientific knowledge of students in grades 4 and 8. It has been conducted every four years since 1995.

In South Africa, the study is conducted in partnership with the Department of Basic Education (DBE) and the Human Science Research Council (HSRC).

South Africa did not take part in the 2007 assessment. Dr Andrea Juan, a senior researcher at the HSRC, told Africa Check that, at the time, the DBE had introduced various policies to improve maths and science performance and wanted to allow them to take effect.

South Africa resumed participation in 2015. Before this, like the other participating countries, South Africa tested grades 4 and 8. In 2015, however, it changed the academic testing years to grades 5 and 9.

According to Juan, this adjustment led to more meaningful results. “It also enabled us to ensure a better match between the content knowledge presented to learners in TIMSS and the curriculum coverage in South Africa,” Juan told Africa Check.

TIMSS 2015 and 2019 gave learners a "less difficult" mathematics assessment. This was because of the poor performance of South African learners, Juan said. The less difficult exam would allow for a wider distribution in performance, which in turn would permit a closer look at the factors related to performance, such as poverty and language of instruction.

The latest results

The 2019 study found that 63% of South African grade 5 learners did not have basic skills in mathematics and 72% did not have basic science skills.

Both of these figures are higher than the DA claimed. However, as the TIMSS tests are administered in grade 5, Juan said this affected the accuracy of the claim. “In the strictest sense, we can only talk about the findings at the grade 5 [level] with accurate percentages.”

Although mathematics achievement might also be very low at the grade 4 level, “there are no nationally representative studies to measure this”, Juan said.

“The correct statement would be ‘in 2019, 63% of South African grade 5 learners had not acquired foundational knowledge of mathematics. The corresponding figure for science is 72%.’”

It should also be noted that the DA’s claim presented one figure for maths and science, while the TIMSS administers exams for each subject and provides separate results for them.

As with PIRLS, the study found that there was a relationship between the results and the availability of certain assets in the home, such as running tap water and an internet connection.

There was also a link between the results and the fee status of South African schools. The HSRC noted that learners in no fee schools tend to be “from lower-income households, live in poorer communities, attend schools with fewer resources, and are largely taught by educators with less specialist knowledge”.

Conversely, learners in fee-paying schools typically come from middle-class families, have better-resourced homes, and attend schools with better-qualified teachers and an environment conducive to better learning.

Load shedding refers to planned power cuts when electricity demand exceeds supply. As we’ve previously written in a 2023 factsheet on the possibility of a total grid collapse, there’s no simple answer to the question of how much load shedding costs the economy. There have been many estimates, and they don’t all necessarily agree.

In March 2023, the financial services company Investec published a breakdown of the impact of load shedding on its website. It included both figures in the DA’s claim, attributing them to the Bureau for Economic Research (BER) at Stellenbosch University.

Cobus Venter, macro service manager at the BER, confirmed that the bureau was the source of the R300 billion estimate, which was published in a privately commissioned report. He also confirmed that the 5% estimate had been included in the report, but had originally been published by consultancy firm PwC.

The BER told Africa Check that calculating the impact of load shedding on the economy was extremely difficult. Their calculation was based on a measure called “cost of unserved energy” or COUE. This is the estimated cost in rands per kilowatt hour (kWh) of electricity that is not supplied due to outages.

The latest COUE estimate, published by South Africa’s national energy regulator, found that load shedding cost around R140.37 per kWh in 2022, although at the time of the BER’s estimate the most recent estimate available was for 2020, at R101.73 per kWh.

The BER compared this cost to the number of hours of load shedding to estimate a total impact on gross domestic product, or GDP, arriving at an initial estimate of R825.7 billion. PwC used a similar method to estimate that load shedding “reduced real GDP growth by up to five percentage points in 2022”.

The GDP is the market value of all goods and services produced in a country over a given period, usually a year.

However, there were many other factors at play. The BER adjusted its estimate to take into account the reduced economic impact of load shedding at weekends, public holidays and outside typical working hours. Its cost estimates fell to between R254.8 billion and R383.4 billion.

‘The cost is immense no matter how you look at it’

The BER told Africa Check that its 2022 estimates were “dated” and stressed the difficulty of calculating the economic impact of load shedding, especially as it was “near impossible” to account for the impact of load shedding on investment in the country.

Venter said: “It is very difficult to estimate a counterfactual but the reality is that cost is immense no matter how you look at it.”

The BER referred Africa Check to other estimates. The South African Reserve Bank used three different models to calculate an estimated impact on GDP in 2022, ranging from 0.7% to 3.2%.

The economic impact of load shedding is multi-faceted, and estimates vary. Nevertheless, the DA’s claim is based on thorough research, and so we have rated the claim as mostly correct.

The World Health Organization (WHO) collates data on the ratio of medical doctors to the general population.

According to the most recent data, South Africa had roughly 8.09 doctors per 100,000 people in 2021, while Brazil had 21.4.

This translates to 0.809 doctors per 1,000 people in South Africa and 2.14 doctors per 1,000 people in Brazil, suggesting that the DA’s figures are only slightly off.

However, data for 2022 is not yet available, a WHO spokesperson confirmed to Africa Check. The 2021 figures cited by the DA were the latest supplied by member countries themselves, they said.

No recommended ratio

Direct comparisons, as in the party’s claim, are also challenging. The WHO has previously told Africa Check that “a country’s number of healthcare workers should be adapted to its needs and the characteristics of its national health labour market”.

When we contacted the WHO about this claim, they reiterated that benchmarks “should be treated as indicative for global monitoring, not for planning at country level”.